Van Life in Maine

My 2024 summer/autumn travel adventures kicked off with a week in Acadia National Park with my long-time good friend, Kevin. More than three decades ago Kevin and I drove from Phoenix, Arizona to Pullman, Washington as a win-win favor for a friend who needed to get a car to the Northwest, It was a quintessential road trip for a couple of college kids before starting our summer jobs. We visited Grand Canyon, Yosemite, Zion and several more national parks, caught a baseball game at Candlestick Park in San Francisco, I think there was a strawberry festival somewhere in California we happened upon. When camping wasn’t an option, we slept in the car -- a non-roomy Volkswagen Jetta -- because this was a phase of life where it was rational to do so. I remember we had one harrowing night in motel outside Vegas or Los Angeles, the kind that yanked us from our young naivete and showed us a grittier pocket of the world people were living in. I don’t recall how we found this place – this was well before internet and cell phones – but I’m sure price was the biggest influence. While there are several details I don’t remember about the trip now, I do remember the car owner’s dismay that we drove more than 2,000 miles for a trip that would otherwise be about 1,400 miles if driven directly. I thought we had a mutual understanding about what comprised the “win” for our side of the “win-win” arrangement, but we didn’t recover from the lack of understanding and eventually fell out of touch.

Kevin and I met in college, and by coincidence, our moms attended Pullman High School together in the 1960s. Knowing Kevin’s parents well, I have no doubt his mom was likely a good student, obeyed the rules, and probably did a lot of “smart kid” things like joined clubs and avoided cigarette smokers. My mom, well, she was once brought home by Pullman cops for riding inside a dryer at the laundromat, in an era of dryer technology where you could press the button with the door open and the dryer would spin. Needless to say, our moms didn’t run in the same peer groups, but it was a small town, and everyone knew everyone. Kevin’s mom is cautious with her words when recalling what my mom was like in high school, carefully describing how surprised she felt when she learned she and my aunt, who, like Kevin’s mom, was a rule follower, could possibly be related.

That western U.S. road trip laid the foundation for several future adventures and trips – Kevin once passed a kidney stone curled up in the bathrub of a cabin in the shadows of Colorado Flatiron mountains -- and 33 years later we were at Acadia National Park. Our willingness to sleep in a vehicle has new thresholds, from Jetta to Sprinter van, the ones the size of an Amazon delivery vehicle. On the infrequent occasions I drive a large UHaul truck or tow a trailer, my shoulders tighten, I get annoyed by someone talking and sabotaging my capacity to focus. I continuously wonder if I overlooked a pin and the trailer might unhitch and go on a journey of its down. I hate the feeling and I hate how irrational it is, as someone who generally operates in a rational way of thinking. I felt like a Sprinter van might be within my limited emotional capacities, like I might not be fighting above my weight class.

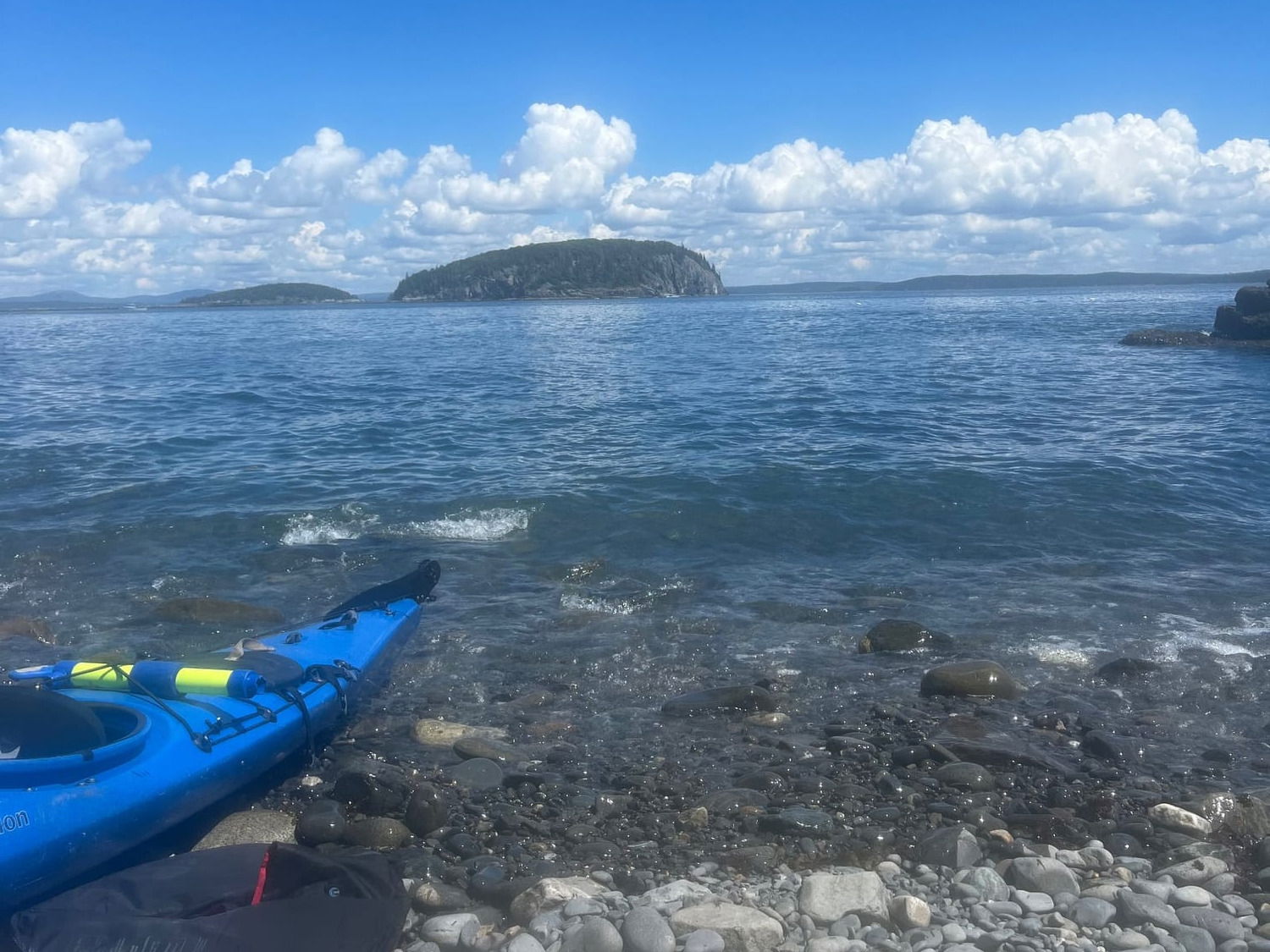

Acadia is located on the coast in Maine, and as such, it’s not a park I figured I would get to as an add-on to another trip to the region given how far Maine is from the main geo-centers of my life. If I was going to see Acadia, it would likely need to happen as a stand-alone trip. The seeds for this trip were planted decades ago; I remember reading about the park back when I subscribed to hard copies of Outside Magazine, sometime in the 1990s when that subscription was among my first luxuries following the start of my first post-college “real job”. I can still picture one of the photos in that article of a couple of sea kayaks on a rocky beach. Living in Seattle where I had taken some kayaking skills classes and led a few trips for a local outdoors club, I remember thinking I should visit Acadia.

Acadia was the first U.S. National Park established east of the Mississippi River, in 1916. A lot of its history is framed around its unique beginning when a small number of wealthy northeastern families like the Rockefellers owned summer houses on Mount Desert Island and were concerned about development. You know, the same kind of development they themselves had contributed to, which they were now concerned about, presumably without seeing the irony. They and others on Mount Desert Island joined efforts to gift 5,000 initial acres of land to the federal government for protection, and over the years continued to persuade neighbors to do the same, maybe at some of their fancy get-togethers. Timing was important here, as this was also an era when some of those who had amassed fortunes and also planted the early seeds of large scale philanthropy, and it was catching on among the nation’s elite. Some families donated some of their land and money, and others didn’t. Today the park stands at 47,000 acres, but it’s not all contiguous. Small pockets of Acadia National Park exist all over the region, sometimes as small parcels on small island off the coast of the “main” park on Mount Desert Island, a representation of the “some did, some didn’t” participation levels in donating land and money. There are stretches of roadway where you regularly enter, leave, re-enter, and leave again. There appears to have been a decent amount of money spent on signage letting you know if you are, or are not, in the park.

Of course, the history of this land predates the Rockefellers and their peers. The Wabanaki Confederacy lived on this land for an estimated 12,000 years. This part of history is an example of one of the messier but common stories the National Park Service is challenged with telling. The National Parks Service is one of the few widely respected federal government agencies, and that is saying a lot given prevailing views of federal government these days tend to settle between “utterly reviled” and “barely tolerated.” Our National Parks protect some of the country’s most incredible and awesome landscapes, places that impress, humble and inspire us, places that protect truly wild environments that remain ecologically intact and provide a safe home for wild creatures to thrive.

But the origins of our National Parks came at a dire cost to the first human inhabitants of these landscapes. We’re familiar with the general storyline: settlers arrive, they go on the move with wagons full of provisions and ambitions, and over the course of ~60 years and with the backing of the U.S. government, they undertake the means necessary to “settle” regions consistent with the vision and ethos of manifest destiny. The atrocities occurred over a longer period of time, but really crescendo'd in the manifest destiny years of the mid 1800s. Millions of native people were violently displaced and an estimtaed five million were killed -- their cultures and practices deemed unworthy by any colonial measure. The mindsets, power and policies that underpinned manifest destiny were part of the foundation that led to a system of federal government land protection, including our National Park Service.

Our National Parks are among the most visited attractions in the country, with more than 325 million visitors in 2023, or about 650,000,000% more people than visited my house. Disneyland and Disney World combined had 86 million, to put the National Park number in a more comprehendible context. And they are treated to some stunning landscapes, views and facts. Standing at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, as much as 6,000 feet deep and 18 miles wide, with literal representations of 5-6 million years of time in its geologic layers, reminds us that we are mere specks on this planet in both a temporal and geographic sense. I don’t know how to describe the feeling, but each time I’ve been to the Grand Canyon I feel an emotion that isn’t familiar, an emotion that tells me if the Grand Canyon were alive, it wouldn’t even register that I’m there, we are such a fraction of a second of its history. It’s almost a feeling of being mocked for how short our lives are, but that is also the upside: it reminds us that life IS short. Live it well. Stop worrying so much.

I don’t know how a National Park should tell the full story of their parks’ history, but I think the sentiments emerging in recent years is accurate, that the story needs to be told better and more honestly. I don’t know how we ever achieve justice, in the non-legal sense of the word, for actions that led to our National Parks, but better stories might help us experience parks, and maybe our lives, with more humility. If I had the proverbial one wish from a genie it might be to bring more humility to this planet to quiet us down and draw less attention to our lives, because history is full of people and communities that experienced unthinkable hardship just trying to live theirs.

I’ve veered off course with this reflection, but I think some veerage is allowed in this type of writing.

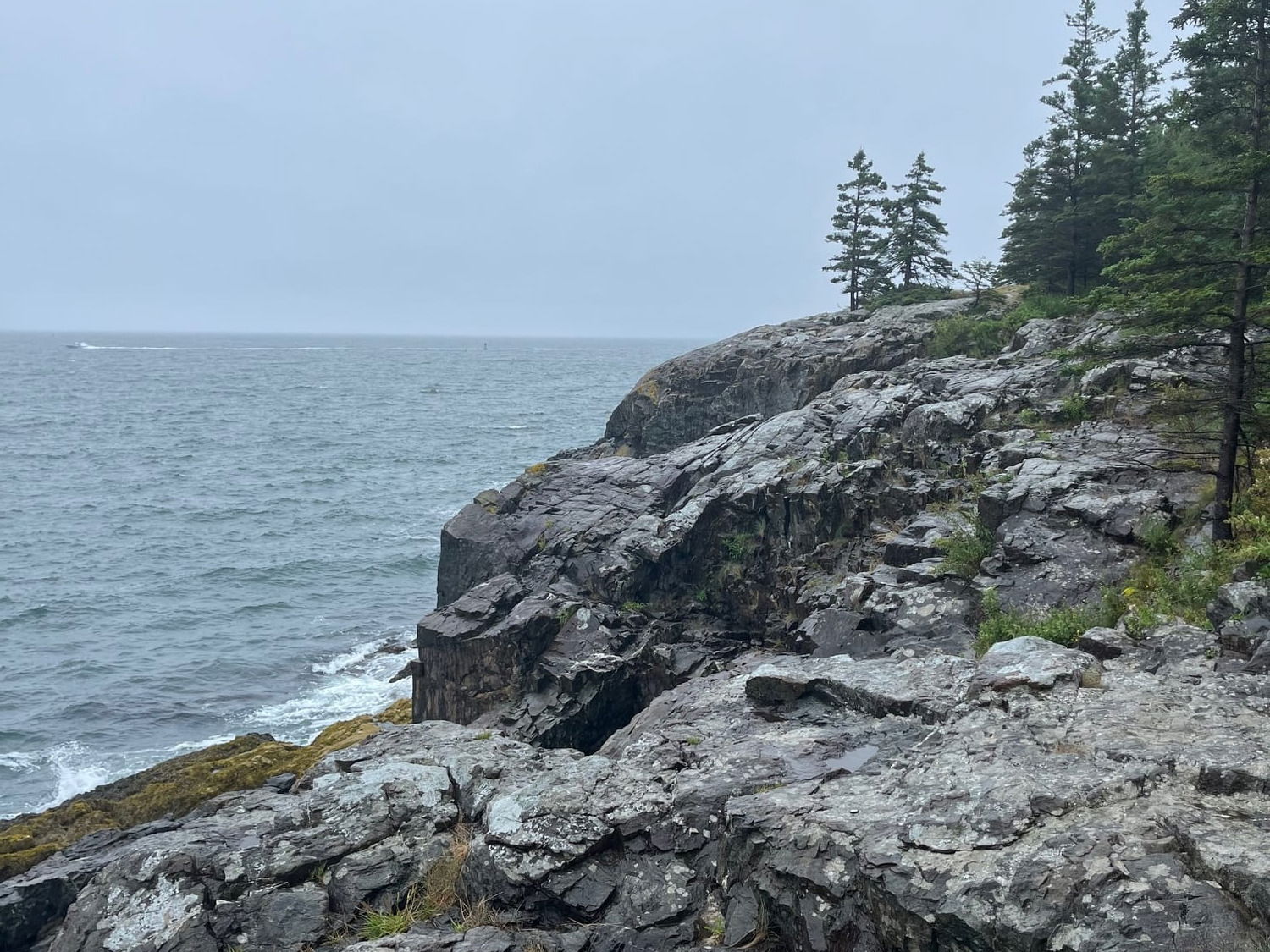

Acadia, overall: LOVED it. A recent graduate student in a program I led had a lot of familiarity with the area, and Zak set us up with recommendations for hikes, taverns with lobster rolls, and cafes with the world’s best blueberry pancakes (Zak’s description). His recommendations were all on the spot, and became our de facto guide after the first day. We took several hikes and rewarded with incredible views past the islands that dotted the coastline and extended to the horizon of the Atlantic Ocean. We sea kayaked and felt the intricacies of the ocean’s movements. We took a plunge in a waterfall pool, prepared good dinners with basic cooking supplies, and one night, while walking the mile back to our campsite from an unstaffed for-profit shower facility ($1.75 for an unknown period of time), I convinced Kevin to walk through an adjacent cemetery. The setting was TOO perfect to pass up given the darkness and fog the surrounding forest had produced around us. Kevin was a reluctant participant, he didn’t like my “Scooby Doo” mentality, worries that curiosity could lead to some kind of mess to untangle. It didn’t. No ghosts, headless horseman, or mysteries to solve.

In many ways Acadia National Park reminded me of the San Juan Islands, north of the Seattle area where I grew up with the added flare of a lobster fishery. This might be one of many possible sweet spots when traveling, when a place has an unanticipated familiarity that it stirs up nostalgia or memories of someplace else, and gives us a sense of calm and control, but different enough that it's still novel and broadens our understanding of the world.

A week later I would be visiting the west coast of Sweden, and experience this again while walking around several rocky islands that reminded me of Acadia. And I loved the Sprinter van, remained emotionally calm at the wheel the whole time less a short period of a driving rain storm on a winding road.

August 2024