Spend Time in Nature

Growing up, my summers were spent with my grandparents, three siblings and two cousins, piled into a log cabin of around 800 square feet in rural central Minnesota. Great-grandparents I never met originally purchased the land and built the cabin in the 1930s, and my dad spent his summers there as a kid too. He remembers the long trek in an early model Ford with his parents from their home in St. Paul – this was before elaborate interstates and highways -- to spend weekends at the lake. One of my dad's earliest memories as a toddler was my his mom and aunt dancing around the yard, having just received the news about the end of World War II. Memories from the lake can run deep.

The tradition continues today among myself and siblings, although none of live in Minnesota, so "going to the lake" requires flights and rental cars, or long 15+ hour drives. My niece and nephews are the fifth generation to create summer memories from Big Birch Lake.

The specific location of the cabin is right in the middle of nowhere. The town of Grey Eagle is three miles away, and for the entirety of my 50+ years of memory of the place, its main street has not extended beyond its present-day three blocks, and reliably consisted of a hardware store, funeral home, and a bar, while diners and small grocery stores have come and gone. To fill the gap and inconsistency in services, the gas station has diversified its offerings; you can special order a cake, buy a take-and-bake pizza made somewhere and somehow at the gas station, and also pick up a container of night crawlers.

The cabin was rustic and tight. The bedrooms were furnished and designed to maximize sleeping capacity, not for hanging out. There was no telephone, and we had a black/white television with one local news station where I remember the weather forecast typically and strategically covered a generously wide range of possibilities: partly to mostly sunny with highs in the 80s and 90s and a chance for thunderstorms.

Originally the cabin didn't have indoor plumbing but that changed in the 70s. A bathroom was added to supplement the outside “privy,” which is Midwestern vocab for “outhouse.” The privy burnt down in the 1990s in my dad’s attempt to smoke out chipmunks who had taken up their winter home in the privy’s vent. Ironically, the word "privy" also means "secretive" or "private," ironic because our privy included a bench seat with side by side toilets. To be clear, the “toilets” were just holes in the plywood bench, each cut to the size of an adult buttocks, which required a sort of ‘half on/half off’ strategy for us kids. The two holes were separated by maybe a foot or two, and in my lifetime, we never had a scenario where this arrangement was useful, where two people needed a to sit down on a toilet so urgently that they were willing to do their business simultaneously alongside someone else. I would rather take my business to the woods rather than be propped next to someone.

Our grandparents gave us an unimaginable amount of freedom to play and roam, especially by today’s standards. We had a lot of options to explore. There was the lake of course, as well as woods, fields, gravel roads that led to more gravel roads, and more. I remember my grandpa as a de facto naturalist, sharing his knowledge about the various creatures that swam, flew or scurried around, and his love/hate relationship with squirrels and chipmunks, who would sometimes enter his garage, which my grandpa interpreted as a threat. If you know much about rural Minnesota culture, a man’s garage is his kingdom, and small mammals are enemies when inside the kingdom.

Grandparents, siblings, cousins and me with a pronounced bowl cut, sometime in early 1980s.

The freedom extended to us by our grandparents led to an abundance of invention and imagination. We became explorers, detectives and outlaws. One summer afternoon while the Olympics occurred somewhere in the world, we raced sticks from our dock to the neightbor's dock via rigorous kicking to create movement in the water, or what amounted to an Olympic stick race. I remember Turkiye won one of those races, and an ensuing argument with a cousin about whether there was actually a country named Turkiye. Decades later I remember constructing small boats with my nephews and niece using whatever materials we could find lying around. Once my dog deduced that each boat was populated by a small number of Goldfish crackers as captain and first mates, he sabotaged the boat race and ate them.

All that time running around nature without restriction probably has something to do with my affinity for the outdoors today and settling into a career that contributes to protecting nature. That’s not reckless speculation, though; research that started decades ago supports the premise that time spent in nature as a child can lead to taking action on nature’s behalf, called significant life experience. Louise Chawla established this as an area of study, and when my own academic career was getting started in the 2000s, I had the good fortune of crossing paths with her several times. Her work on significant life experience has held up over time; studies today continue to illustrate a connection between time spent in nature during youth, and a commitment to nature later in life.

After graduate school, I stayed at Colorado State University as director of the university’s nature center located a few miles off campus on 200 acres. My ambition was to be at the helm of putting this research into applied practice, to facilitate those pivotal significant life experiences in nature for youth, and hope it would lead to their future commitment to nature, as Louise Chawla’s research says it should. That was our driving purpose, to connect youth to the natural environment.

You know you’ve had substantial time on this planet when you learn about trends not by reading about them, but instead observing the trends first-hand. That is my experience with the study of children and nature. It started with Chawla’s work, research that first circulated mostly among second tier academic journals and conferences, often by people like myself trained in social sciences and giving the research a good effort but relegated at times to the shadows of other research about conservation and nature.

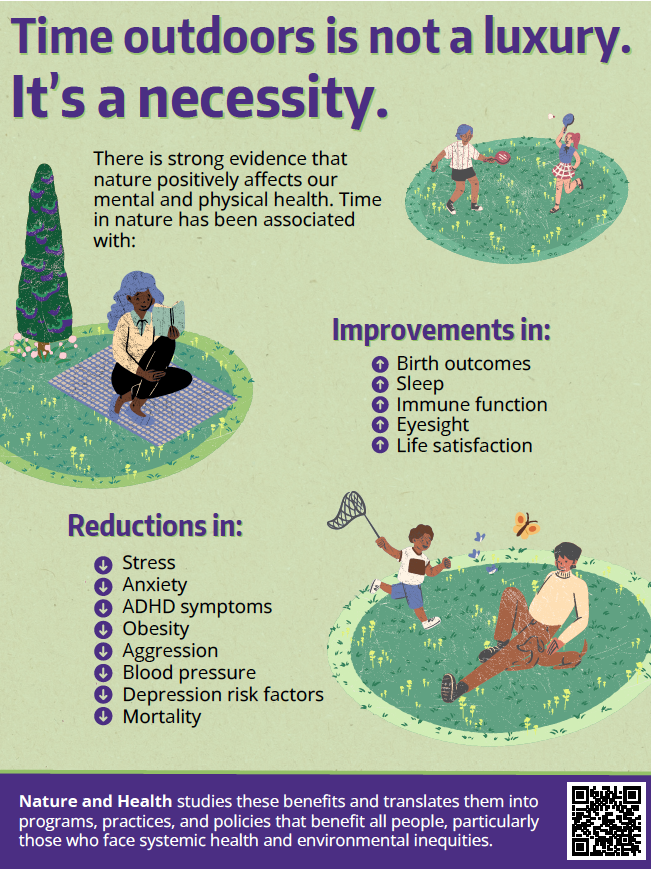

Chawla’s work about the benefits of nature has since exploded into spheres and disciplines we only dreamt about when I first started this work. Today, studies about children and nature are led by and circulated among physicians, public health administrators, epidemiologists, mental health experts, cognitive psychologists, and others. It is deliberated within the most respective scientific professions: public health, pediatrics, and more. People with similar backgrounds as myself partner with physicians and psychologists to study the benefits of nature. It is a completely different landscape of research than where it was 20 years ago.

As an example, the University of Washington hosts the Center for Nature and Health, an interdisciplinary academic organization of ecologists, pediatricians, public health experts, conservationists, public policy advocates, and community planners. Their work (and others) has generated a body of research in science and medicine globally that describes the health and developmental benefits of time spent in nature, especially with kids.

Taking a walk in the woods isn’t just a benefit for "outdoorsy” people who need to get their fix in nature. As little as 20 minutes of undistracted time in nature has been shown to reduce stress, blood pressure, heart rates and blood sugar, improve attentiveness, focus and memory, and enhance well-being and happiness more generally. The list of mental health conditions for which nature exposure has been shown to be an effective coping strategy includes depression, PTSD, loneliness and anger.

It achieves this via its positive regulatory impacts on our sympathetic nervous system, the part of our bodies that sorts out if we are stressed or calm; it's the same systems activated when we feel 'flight or fight." Time in nature is shown to have a calming or slowing effect on this system in as little as five minutes of nature exposure.

All those years as a nature center director when our goal was simply to plant the seeds for future environmental behavior, we were also improving the health of youth and their families in very important ways. We had no idea!

What I love about this research on the benefits of nature is it broadens the relevance of natural spaces to a much, much wider swath of our community and its policymakers. We have solid evidence now that protecting or restoring natural spaces is a great strategy for healthier people and communities, outcomes that are relevant to just about anyone who cares about themselves, their families and the places they live. This brings a lot of people into the discussion about protecting natural spaces. It is no longer a discussion limited to outdoorsy people; it's relevant to all of us.

Many studies about the benefits of time in nature occurred in neighborhood parks and similar urban settings, not in far off rugged wilderness with outdoors fanatics with specialized gear and endurance. A walk in a local park a few times a week for as little as 20 minutes can get the job done. Go to the park, keep your phone tucked in your pocket, and make the experience about your health. You will be healthier and happier, and maybe become a stronger advocate for public land as well.

Top of page photo: Dolomite region, Brennero, Italy