The Myth of Multi-tasking

Note: since multi-tasking is applicable to both work and non-work lives, this same post shows up in two places on this website.

One of the cleverest tricks our brains have played on us in our world of devices and rapid paces is convincing us we can multi-task, that we can do multiple things simultaneously and do them well. I fall for this a lot, in part because I love the feeling of being productive. A Saturday morning kicked off by a trip to Ace Hardware and a half dozen small projects….so good. And I love a good deal, and multi-tasking feels like a 2-for-1. But it’s so, so bad for us. People who study multi-tasking repeatedly conclude that the opposite of what most of us probably think is true about multi-tasking; in fact, the whole notion of multi-tasking is mostly a fallacy. We don't actually do two things at once. Rather, we’re shifting our cognitive attention from A to B, then back to A, but we’re usually not (cognitively) doing A and B at the same time. It’s one reason driving and texting is so bad; our brains actually “leave” driving in order to focus on texting. We might physically be steering a car and sending a message at the same time, but our brain can only gives it attention to one.

Gloria Mark is a leader in this area of study. She wrote a book called Attention Span, and has been all over the media and podcast world as an expert on multi-tasking. Her research is so relatable; when I’ve listened to her interviews I’m constantly thinking about examples from work where multi-tasking is practically expected, and I would say it’s even rewarded. Especially email. I’m at a point where I think of email mostly as a saboteur of productivity and a villain trying to pull me into the destructive world of multi-tasking. Higher education, my field of employment for the past 20 years, is absolutely manic about sending emails. In the first few months of Covid, I tracked how many emails were sent on matters related to the virus, and then copy/pasted the emails into a Word doc. The weekly average for the first 6 months was a staggering 42 emails and 36 pages of text. Ironically, a significant number of those emails opened with an attempt to sound empathetic about the new demands on our jobs. You know, the demands of reading volumes of new emails.

A guaranteed way to trigger some fire in my veins is to send me an email, and the next day send me another asking whether I received the first one. Of course I did. That's precisely how email works; it's a send/receive sorta thing going on there. The actual question implied in the follow up is "Although I have no idea of your work demands over the previous 24 hours, why hasn't my email been a priority?" As you can tell, it's a sore spot for me.

My point -- prior to my mini-rant -- is email promotes multi-tasking, often because the volume of email leads us to always keep an eye on the inbox so there's no big pile-up of messages to deal with later.

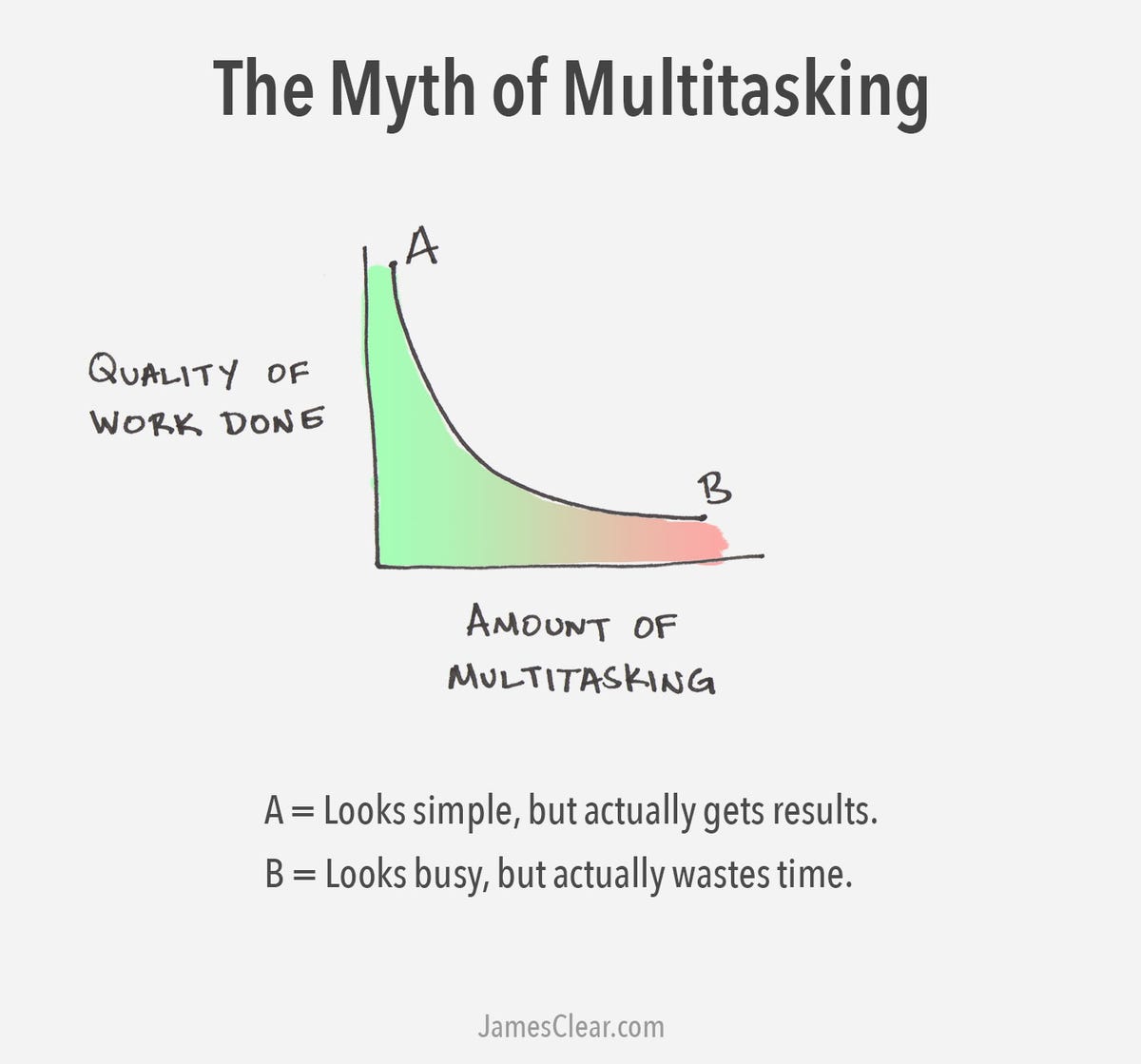

Here are the consequences of multi-tasking: 1) we are less productive. When we shift from one task to another, there is a “restart” required – researchers on the topic call this “crossover time". If you stop writing a report to respond to an email, it takes a moment to reset your brain before picking up and carrying on with writing the report. The result: longer time to write the report than if you had just written it at once. 2) multi-tasking leads to mental fatigue, and even stress and anxiety if we’re chronically multi-tasking. The constant pace of starting, pausing, and restarting requires a lot of effort from our brains over the course of a day. And eventually, our brains get tired and need a rest, but that point might come in the middle of the day when we don’t want, or can’t, give our brains a rest. Ever have that moment at the end of a day where you take 10-15 minutes and collapse into a chair doing literally nothing, and it feels SO GOOD? That’s giving our brains a rest (and a good strategy to prevent stress; give your brains a rest!). 3) there can be very real consequences to some multi-tasking scenarios, like texting and driving. According to a Freakonomics podcast, I believe it was upwards of 50%+ of participants in a survey claimed they were good multitaskers. And while it’s true that it is possible to be a proficient multi-tasker, it’s only about 2-3% of the population, and they are exceptional: for example, elite athletes, world renown composers, and others that most of us can only dream of being.

It's probably wise for most of us to accept that we are not good at multi-tasking and adjust our lives to that reality. It is simply not good for us; don't tell yourself otherwise. You'd be at odds with actual science about the topic.

A few tips from the experts on how to manage ourselves in a world that wants to trap us into multi-tasking:

- set small chunks of undistracted time when working on a task. Close your office door, put your phone out of view, and tell yourself the next 30 minutes will be devoted to Task A, and nothing more.

- check email a few times per day, but don’t keep it open all of the time.

- set time blocks with your team where nothing will be scheduled or sent, such as a few hours on a given morning each week.

- deny yourself the opportunity. This is sort of like the strategy of getting rid of all the junk food when trying to get healthy. Don’t bring your phone to a meeting. Turn off the second screen during a Zoom call. Don’t even make it an option to multi-task.

Cover image AI generated via Canva Magic Media.