Kindness

There’s a young man, Benedict, from Kenya who I’ve known for 15 + years. He has often supported groups of students I co-led for a short-term study abroad experience, and he is truly one of the kindest people I’ve ever met. His days are lived through a filter of nonstop surveillance for how he can be helpful and kind to others, in ways that go beyond typical support for a camp full of new visitors. He works tirelessly to make sure everyone is comfortable, full of good food, equipped with what they need, and given an answer to every question they have. I rarely see him take time for himself. For Benedict, life is always, always about kindness to others.

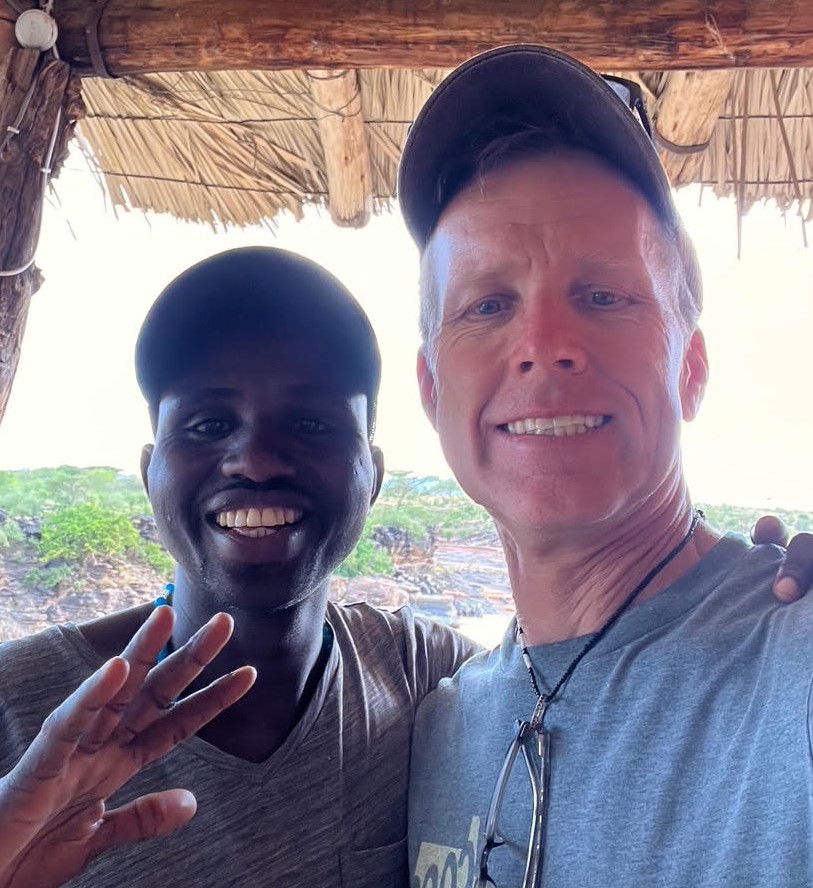

Benedict (left), a world leader in the delivery of kindness!

After researching kindness, I’m left wondering how much better our lives and communities would be if only we could fix the flawed perceptions we have about a few aspects of kindness, and live more like Benedict. Similar to research I covered in other posts about gift giving (we focus on the wrong stuff) and humility among organization leaders (we think it’s a liability for advancement), we tell ourselves a story that isn’t true. If we got it right, the benefits could be substantial.

I'm going to give just a quick summary of the well-being upside when we act with kindness because it's straight-forward and easy to summarize: to the person who acts with kindness, the research is clear that acting with kindness makes us feel happy, increases positive emotions and decreases the negative ones, and overall, is good for our well-being. In fact, doing something for others often produces more positive outcomes than doing something for ourselves! But as the flawed creatures we are, we talk ourselves out of being kind -- like so many other behaviors-- despite its healthy benefits.

I read some of the articles in my prep for this post just prior to a short walk to a nearby hardware store, and that primed my brain to notice or think about acts of kindness during while out and about. The store didn’t open until 9am – I thought it opened at 8am – so I killed about a half hour at a coffee shop on the same block. The barista was notably friendly to every person in line ahead of me, the kind of friendliness that transcends customer service and feels notably and happily different. He acted similarly when I ordered and asked about my plans for the day – my plans were for a day of dabbling in house projects, as I come from a long line of central Minnesota dabblers, a hotspot for people who tinker, putter and dally above their skill level. My dad, in an attempt to deal with the relatively minor matter of a chipmunk burrow in the outhouse at the family lake cabin, overshot the problem-solving and burned down the outhouse.

I carried on with the barista over the few minutes while my drink was made, and as he handed it over, he wished me a day of successful house projects, indicating he either had no idea about my actual track record on house projects, or he had a very correct idea and was wishing me a better-than-usual outcome, but no project has ever gone so awry that it ended with something in a pile of ashes.

I sat at a table and overheard the barista act similarly to every customer, often adding compliments – he liked a customer’s coat, congratulated a parent for their daughter’s college graduation, expressed a rousing “looking younger than ever” sentiment when a regular customer stepped up to order. In each instance, a short conversation followed, a conversation that felt more than obligatory or transactional; rather, the conversations seemed sincere and kind.

This barista, like Benedict, is an outlier to studies about kindness. Research suggests most of us would act differently toward strangers because we underestimate the benefits of a compliment or a similar act of kindness, or we think it will feel awkward to the other person, or we are just too anxious and in our own heads about it all. It’s really not that complicated, we just make it that way. One research study concluded that we think we are too incompetent to give a compliment, and therefore, are reluctant to give compliments. So a quick sidebar, here's how to give a compliment: "Hi, I really like your _____."

In the very short walk between the coffee shop and the hardware store, I quietly walked by a person I assumed was homeless, sitting bundled up in blankets in the covered area of the entry to a restaurant that would open several hours later. I wondered if they would have any friendly interactions like the ones I observed and experienced in the coffee shop, and then wondered why I didn’t initiate such an interaction myself. I'm the incompetent or anxious person in the studies, perhaps. People experiencing homelessness often just want a smile or small expression of empathy from passersby.

Let’s drill down on some of the research. Understanding kindness, according to some researchers, consists of estimating the cost (time, effort, financial) to the person undertaking the act of kindness, the benefits to the recipient, and a resulting cost-benefit ratio, sort of a return on investment calculation about whether we think the act of kindness will be worth it. Obviously we aren’t this calculated or nuanced when we actually act (or not) with kindness – the cost-benefit deliberation is instinctive or subtle-- but it provides a framework to study and understand the behavior. Of this simple cost-benefit kindness model, the best predictor of kindness are the benefits. That is, kindness is most likely to occur when we consider the benefits to the recipient, and less so the cost to us of acting with kindness (time, money, effort). The benefits predict kindness behavior more than the rest of it. And in what I’ll call a Conclusion Bummer, we get this part of the equation terribly wrong.

Conclusion Bummer #1: We consistently underestimate the benefits of our acts of kindness.

Amit Kumar and Nicholas Epley have conducted several studies about kindness, studies I found both intriguing and creative. For example, in one study participants were given the choice to keep a coupon for a free hot chocolate at a downtown outdoor ice skating rink or to give the coupon to a stranger. Those who gave their coupon to someone else were later asked to 1) rate how the act of kindness felt to them, and 2) estimate how they think the act of kindness affected the receiver’s mood and happiness. Those who gave away their coupon reported higher happiness and fulfillment than those who kept the coupon for themselves. But they also consistently underestimated the effect of their generosity on the recipient, compared to what the recipients reported.

In a very simple act of kindness – giving a compliment to a stranger about their shirt, jacket, dress or similar article of clothing -- the researchers found similar results: those who gave the compliment consistently underestimated how pleased, flattered or happy the person felt after receiving the compliment. Since benefits predict our kindness behavior, and we consistently underestimate those benefits, we have now have our next Conclusion Bummer:

Conclusion Bummer #2: because we underestimate the benefits of kindness, we are led to act less often with kindness.

What accounts for our chronic underestimation of the benefits of acts of kindness? To me, this is one of these “well, of course” moments when researchers reveal the obvious. But sometimes we need a few reminders of the obvious, as indicated by our flawed inclinations. We underestimate the benefits of kindness because we overlook the importance of the warmth expressed by kindness. If we give a coupon for a cup of hot chocolate, we think kindness is essentially defined by the cup of hot chocolate, or sort of a utilitarian view.

The receiver, however, sees the kindness as a cup of hot chocolate AND the warmth (no pun intended, I promise) conveyed by the gesture. Put more generically, when acting with kindness, the giver tends to think of kindness as X, but in the eyes of the receiver, it’s X plus the warmth they felt when they received X.

Anecdotally, it seems to me we frame a lot of our kindness around a utilitarian view and therefore we make it easy to overlook the warmth factor. Thinking about some standard acts of kindness – making food for friends with a newborn, collecting a neighbor’s mail while they’re out of town, buying a cup of coffee for a colleague -- all of these provide something useful to the receiver, and therefore our assessment of the benefits could be understandably tilted toward a utility value. To be clear, I’m speculating here; this “utility” angle isn’t in research I read.

With kindness, there’s also the pay it forward effect. When people are on the receiving end of kindness, they, unsurprisingly, are more likely to act kindly toward others. There’s a bunch of anecdotes about someone paying for the drive thru order for the car behind them, and then it carries on until it gets to a driver that didn’t get the memo. At a Dairy Queen in Minnesota in 2020, this went on for over TWO DAYS and 900 cars, a duration that seems implausible to me for a million practical reasons and ethical sticky moments. “The person in front of you paid for your $4 milkshake. Would you like to pay for the $40 of meal deals for the minvan behind you?”

In another of Kumar and Epley’s studies, volunteers for a research project showed up to a university lab setting, knowing only they were volunteering for a study. Prior to the activity, they received a gift prior to their participation. The study says it was a “gift from the lab store” and while I don’t know what is sold at “lab stores,” let’s assume it was better than a glass tube. Fifty percent (50%) of the recipients were led to believe the gift was from the lab in exchange for their participation, and the other 50% were led to believe it was a random act of kindness from another study participant (the study participant who gave the gift was, in fact, planted by the researchers).

The study directive was simple: participants were asked to distribute $100 between themselves and a second person, in whatever matter they wanted. Participants who received a gift as an act of kindness prior to the study (not as compensation for their participation) were more generous to others, allocating nearly to a 50/50 even split, whereas the others were closer to a 40/60.

Conclusion Bummer #3: in the absence of kindness from others, we tend to also act with kindness less frequently.

In sum, here is the sequence of our Conclusion Bummers: (1) we underestimate the benefits of kindness, and so (2) we are less likely to act with kindness, and therefore (3) others will also act with kindness less frequently. If we can fix #1, then voila, we can U-turn this whole mess we created for ourselves and (1) we accurately assess the benefits of kindness, and so (2) we act with kindness more often, and therefore (3) others will also act more frequently with kindness. What a nifty and no-brainer positive feedback loop we just established.

The implications from this research on how to live are absurdly straight-forward:

- if I may borrow from Nike, we need to just do it. When we think about an act of kindness too much, we miscalculate, we worry about awkwardness, and we talk ourselves out of it.

- start small. Building a habit of kindness starts with simple acts, such as giving a compliment to a stranger. Start with giving a compliment every day, and over time raise the bar

By 100% coincidence, I substituted for a third grade class the same week as pulling together this post, and each student in the class owned a kindness punchcard in which the teacher would acknowledge a student for doing something kind and record it on the card. When full, the cards could be redeemed for a treat or special privilege at some point. Kids are too young, their brains too underdeveloped, their life experience too minimal, to mess kindness up as much as we do as adults. Kindness was everywhere in that classroom; it was so evident in the culture the teacher had created. So many kids always ready to help, clarify the classroom norms and rules, find me a supply, and more. Maybe it sounds cliche, but that's one of the beauties of kids, they don't complicate things via their own over-thinking and internal deliberation, they just act.

Kindness improves the well-being of ourselves and others, and it can be so easily integrated in our lives in the simple ways. Be like Benedict. Be like the barista.