The Great Productivity Killer: Meetings

If a common practice at work reduced your autonomy, increased fatigue, adversely affected your performance and productivity, and potentially put a strain on workplace relationships, it seems like it would be re-evaluated as a workplace strategy.

Yet the use of meetings persists.

If I rank ordered the least favorite parts of my job in higher education, meetings would be the runaway winner, even far ahead of justifying to a skeptical procurement office about why a nature center needs bug spray or completing a required annual training for literally the 12th time. Sometimes while in a meeting coma I would look around and do the simple math of number of people at the meeting x length of the meeting, and cynically wonder how many world record marathons could be run during that collective time.Ten people at 1.5 hours (15 hours), for example, would be nearly 7.5 world record marathons, a much more impressive use of 15 hours, at least by the bored looks or multi-tasking of most people at meetings. The return on investment seems highly circumspect.

Here's a staggering statistic: in the United States alone, there are approximately one billion (that’s right: one billion) meetings a year. I was equally surprised to learn most of them were not at the university where I worked.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) studied the workplace behavior of knowledge workers – people who generate value or workplace performance based on taking action via a deep expertise in a given area – think doctors, lawyers, accountants, engineers – and found that as much as 85% of time is spent in meetings, and nearly three-quarters of meetings were assessed as unproductive and not worth the time, a finding supported by another study by Atlassian. A study by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development found that people in large organizations spent between 17-47% of their time in meetings, and the most common reported barrier to productivity was, you guessed it, meetings.

We sure spend a lot of time doing something we think is a waste. Then again, folding laundry seems like a waste of my time, yet I still do it.

As I’ve stated in other pages, everything is researched. And sure enough, meetings are studied. Imagine, out there in the world of small talk at social events when someone asks “what do you do for work?” there are people who respond with “I study meetings.”

Steven Rogelberg is one such individual. As is often the case when I dig into research about a topic, there are often one or two names that are cited more than anyone else, and Steven Rogelberg is one of those names. A professor of Organizational Science and Management, he’s written several books and a gazillion peer-reviewed journal articles (I stopped counting). Ironically, he also testified to the U.S. Congress in 2022 about how to be successful in difficult work environments, a testimony that obviously did not stick with his audience. I also feel empathy for his graduate students when they need to ask to meet with him; the pressure for that meeting to go well must be nerve wracking.

Joseph Allen and Nale Lehmann-Willenbrock took a big plunge into the presumably lonely waters of the science about meetings and reviewed 253 research publications about meetings - an approach sometimes called a meta-analysis or systematic review – and looked for commonalities and trends in the research. The two undoubtedly must have met a lot to discuss their independent review of the articles, as this research method usually necessitates, and I wonder if any of those meetings, ironically, didn't go well.

Among the results from these leading scholars and others about what constitutes an ineffective meeting, or in plainer words, a meeting that is a waste of time: 1) dominant voices and therefore, the lack of involvement of others, 2) one-way communication, often in a frame of reporting or updating meeting participants, which fails to take advantage of convening people together, 3) lack of clarity about next steps following the meeting, and 4) poor facilitation, the proverbial hamster wheel of relentless and directionless discussion that fails to move the group toward a goal or outcome.

Given this list of culprits of meeting ineffectiveness, the science about what constitutes a productive meeting (i.e., a good use of people’s time) is fairly intuitive: 1) successful facilitation during the meeting by a designated leader to hear from all/most participants, 2) interacting, such as sharing information and perspectives, and acting collaboratively to make decisions, solve problems or set a goal. More simply, interacting is taking advantage of bringing people together, 3) managing time, which means mindfulness about others’ schedules and demands when setting a meeting, selecting the right duration of time, starting and ending as scheduled, and not over-scheduling meetings within a short period of time, and 4) a clear purpose for the meeting, and the purpose is shared with participants in advance. Facilitation and a clear purpose were the most common factors across studies I reviewed.

In an MIT study of 76 companies that implemented no-meeting days each week – at least one day and as many as all five work days – the researchers found the sweet spot of no-meeting days was three. Autonomy, productivity, and satisfaction increased by at least 65%, and micromanaging and stress reduced by 68% and 57% respectively. Subsequent increases/decreases with four and five no-meeting days were small, sort of a law of diminishing returns effect.

Some tips that contribute to effective meetings where people feel like their time was spent well:

- Be clear with yourself and others about the meeting purpose. The purpose should involve solving a problem, making a collective decision, collecting feedback or a similar outcome that requires convening people.

- Before scheduling a meeting, ask if there is another option for achieving the purpose. Several years ago, a colleague I switched to recording a video prior to the start of each academic year to describe the incoming cohort and program schedule. It was one less in-person demand on people’s schedules the week before the semester started.

- Align the meeting duration with the meeting purpose. I would estimate at least 90% of meetings in my life have been scheduled for one hour, for no other reason than one hour seemed to be the norm or what people were willing to give. Whether it was to chart a course for the next five years or plan Helen’s retirement reception, it was always an hour.

- Facilitate effectively. Ask quieter participants about their perspective, ask louder voices to wait, acknowledge and table off-topic feedback, demonstrate active listening as people speak, and periodically summarize what’s been said.

- At the end of the meeting, clarify what will happen next.

- Consider no-meeting days, or start smaller with no-meeting half-days.

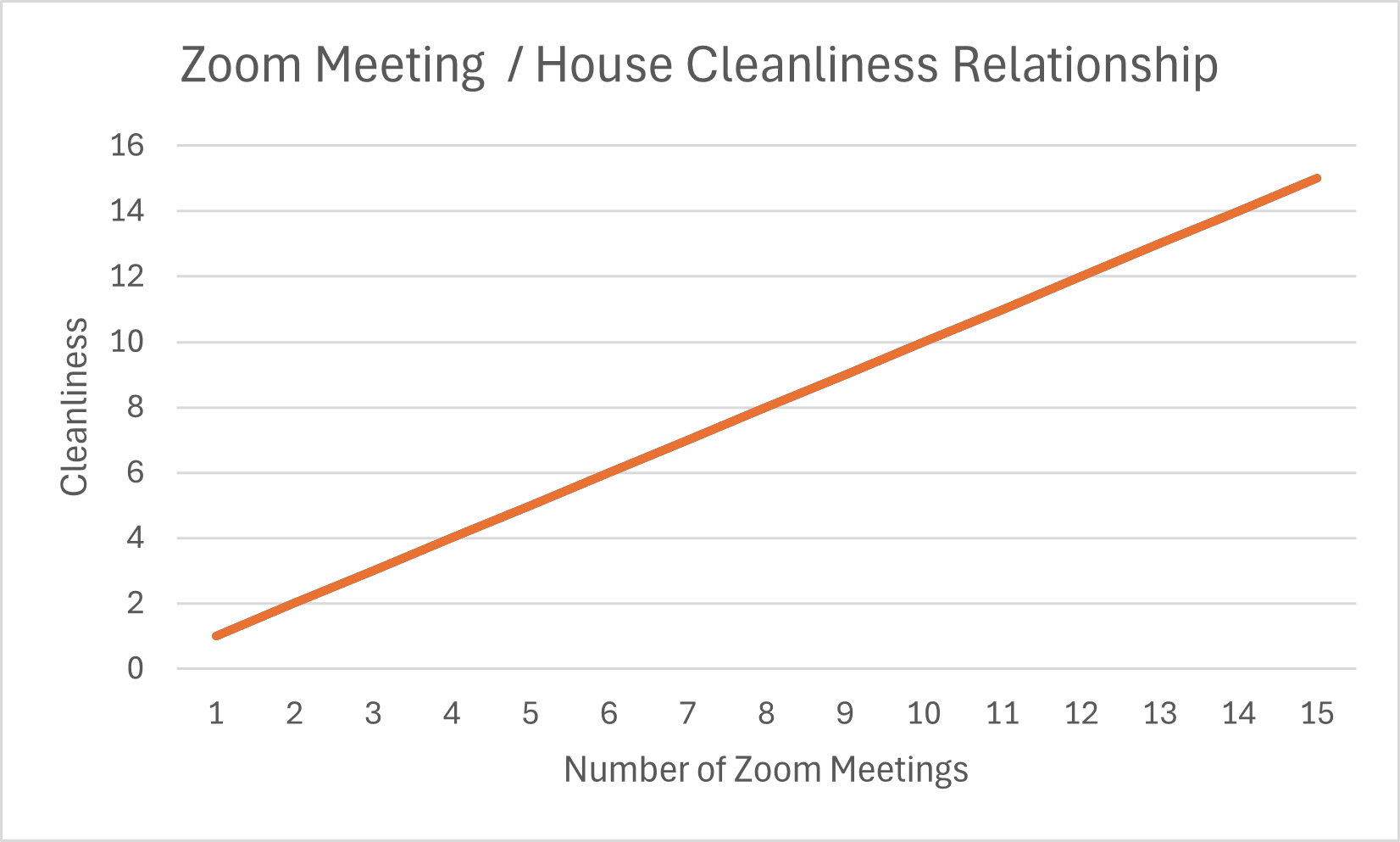

I have one concern with meetings becoming more productive and useful. I get a lot of house cleaning during Zoom meetings with my camera turned off. I mean, A LOT. The relationship is likely a perfect 45 degree line graph.

One of my liabilities is my disdain for feeling like I’m wasting time, and as we have established, most meetings are perceived as exactly that. But camera-off Zoom is like a gift; get the credit for attending while using time to clean stuff I would never otherwise do like wiping down ceiling fan blades and cleaning the underside of a glass coffee table. I’m not a neat freak, or maybe I didn’t used to be, but if I want to maintain this cleanliness, meetings need to stay a waste of time.

Cover image AI generated via Canva Magic Media.